Comparative Literature: Translating Languages with AI

By Kate Barnes

When we think of artificial intelligence, images of big data centers, robots or underwhelming movie magic come to mind. What may not immediately be considered is language and literature – specifically, translation and storytelling.

At the University of Michigan, Christi Merrill is hoping to change that.

Merrill, a professor of South Asian literature and postcolonial theory, is exploring how AI can help language learners become more creative and critical thinkers through novel approaches to using large language models, or LLMs.

LLMs are a type of AI model trained on massive amounts of text data and designed to understand, generate and manipulate human language. This intersection of technology and something so inherently human has fascinated Merrill since her undergraduate days at U-M.

“I first started learning about languages like Hindi and Urdu and quickly became interested in storytelling traditions and the nuance of cultural context,” said Merrill, who is also chair of the comparative literature department.

“After spending some time in India and beginning my work in comparative literature, I noticed just how little information was available regarding translator sources. The humanistic side of the translations really intrigued me, such as considering which available sources inspired these translators’ choices, but so did the lack of data sets with literature in many languages.”

“To really gain the most from AI in comparative literature and literary translation, we need to consider not only the technical aspects of language, but also identify where our biases – or the LLMs’ biases – lie and adjust accordingly.“

As she continued her studies, Merrill focused on reimagining global storytelling, while increasing access to information. She was also determined to strengthen the pipeline of researchers in this area in order to move the field forward.

To that end, Merrill worked with leadership in the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts to hire a postdoctoral fellow. Enter Ali Bolcakan, who is helping Merrill lead the charge to build more robust, equitable and balanced datasets for literary translations.

While working on his dissertation, Bolcakan was examining Greek, Turkish and Armenian languages. He realized that the information he needed was difficult to find digitally because of the way multilingual data is collected, processed, and presented to end-users. For example, he could not use the Armenian alphabet to search for specific texts despite knowing they were available at a library.

“I quickly recognized that anyone who uses AI needs to consider its limitations,” Bolcakan said. “In my experience, when LLMs give you information about a multilingual data source, such as a foreign-language book, they will regurgitate what has been written about that book in English-language scholarship rather than analyzing the source text itself. This highlights the need for nuance and experience to inform the systems of cultural context and understanding.”

Dr. Christi Merrill meets with colleagues to discuss her novel use of AI in literature translation.

Though their disciplines and areas of research may differ, Merrill and Bolcakan found common ground in the issues they were facing in their respective studies. With help from consultants at the Language Resource Center, they also secured funding for their collaborative work through a New Initiative/New Instruction grant, which seeks to support curriculum development and innovative teaching methods.

As a postdoctoral fellow, Bolcakan recognizes the importance of training the next generation on how to build these systems and best utilize them in language and translation-related work. He also highlights how critical it is to value these languages as objects of study in order to make a difference.

“One of the reasons I came to U-M for my graduate studies was because it offers programs and opportunities like this one,” Bolcakan said. “There is a significant amount of support departmentally and institutionally to train the next generation of researchers that, I think, will help carry U-M forward as a leader in the space of using AI as a resource for literary comparison and translation verification.”

Reflecting on her work as a professor, Merrill recalls a paradigm shift between technology and the work she was doing in comparative literature. There was a noticeable change in how she, her colleagues and her students could disrupt the hierarchy of languages that was causing bottlenecks in these LLMs.

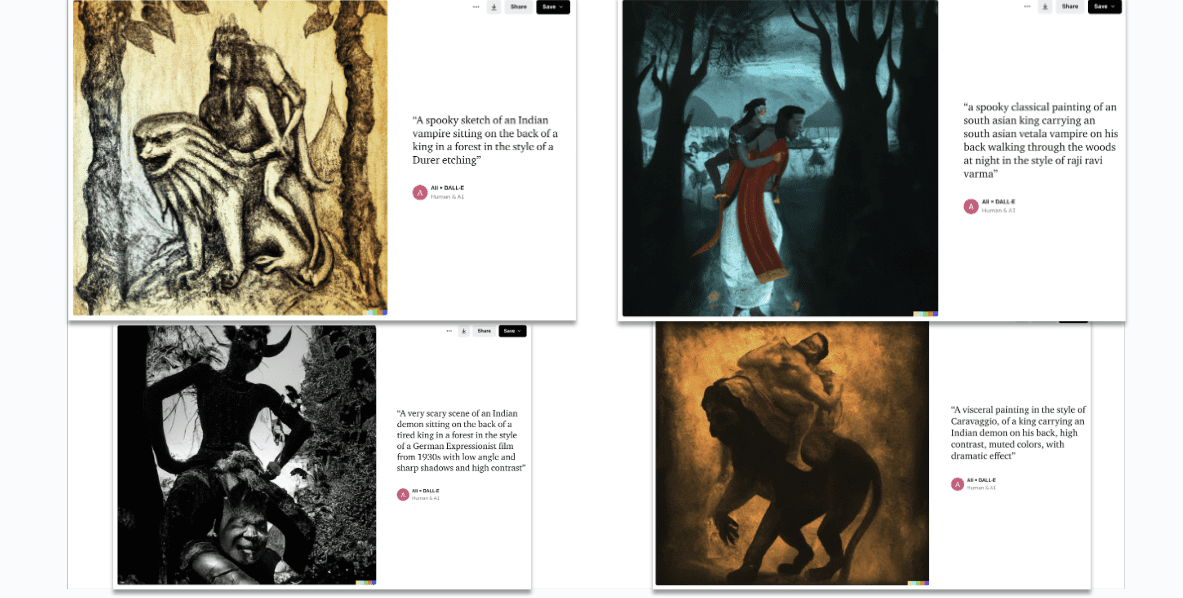

To highlight the shift, Merrill asked her class to create an image, using AI, by prompting the system with different translations of a similar fantastical character – the vetala.

The vetala is known as a spirit or ghost in many South Asian literatures and is often described as a malevolent entity that inhabits and animates corpses. She challenged her students to use different languages and versions of the same storytelling cycle.

Merrill asked her students to approach the project with the goal of better understanding the human response to literature, asking themselves why they feel the way they do about certain translations or interpretations. Then, using that thought process, they were to build better prompts for the AI.

The students, choosing from multiple languages and sources that reference the character, interpreted the descriptions on their own and used those to generate the image. It was an intentionally iterative process that encouraged students to think creatively in their prompts.

The results? The images were vastly different, not because of a lack of imagination on the students’ part, but because of the limitations and biases of the AI.

Merrill’s student images generated by AI after prompting the system with different translations of a similar fantastical character – the vetala.

“To really gain the most from AI in comparative literature and literary translation, we need to consider not only the technical aspects of language, but also identify where our biases – or the LLMs’ biases – lie and adjust accordingly,” Merrill said.

“This combination of human and tech has brought about fresh and unexpected connections to language, imagery, literature and storytelling, which is the whole idea. There is a lot of misconception about how AI will stifle creativity. However, I am seeing the exact opposite. By approaching literature and language with creative and critical thinking together, we can expand our collective imagination and knowledge base, discover fresh perspectives and better understand cultural nuances.”